Since buying Safe Harbour three and a half years ago, I’ve been fortunate to spend each summer cruising British Columbia and Alaska. As spring rolled around I’d let the marina know that May would be my last month. And each fall I returned and lived aboard through the winter, spending most of my time at the dock.

This winter was different. Unlike my previous job, working on Slowboat doesn’t mean I need to be in one place. I knew I didn’t want to be in Anacortes all winter (something about a girlfriend in Seattle and the thought of all those hours on I-5…), but I didn’t know where I did want to be. So I did the only responsible thing: I got no slip at all. That’s right, I’ve been a transient all winter. And it’s been awesome.

I haven’t been cruising like I do in the summer. Besides a month-long jaunt to Princess Louisa Inlet, including a bunch of time in the San Juans, I’ve been wandering around Puget Sound, rarely venturing more than a few hours from Seattle. Instead of moving every day, I’ve been more likely to move a few times a week. About half the time I’ve been in Seattle. The rest of the time I’ve been at Blake Island, Eagle Harbor, or Port Madison, or less frequently, Gig Harbor or Poulsbo or anchored out somewhere.

Even though this winter has been particularly cold and rainy, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed my nomadic life on Puget Sound. I’ve woken to a fresh blanket of snow at Blake Island and on Lake Washington. I’ve seen orcas swimming just off Shilshole and countless sea lions resting on buoys. Breakfasts (yes, plural) have been interrupted by eagles screeching as they flit this-way-and-that, dodging aggressive ravens. Anchorages, parks, and marinas that are chock-full all summer sit empty through the winter.

What are the keys to making this all work? Finding affordable transient moorage and being as self-sufficient as possible.

Transient moorage is typically a dollar per foot per night or more. Power is extra. It’s not uncommon for the nightly total to be at least $60 (slips rented by the month tend to be about 1/3 the cost, per night). Multiplied out by 30 nights a month, transient moorage quickly becomes a major expense. Two things have dramatically reduced transient moorage costs: an annual Washington State Parks annual moorage permit (unlimited moorage at Washington State Parks), and membership at Seattle Yacht Club.

If you’d asked me five years ago if I’d ever join a yacht club, I’d have laughed. Yacht clubs were for people with, well, yachts. Yacht club people wore blazers and ascots and turned up their noses at those of us on little boats. But Bob Hale, who created the Waggoner Cruising Guide, convinced me otherwise. He’s a long-time Seattle Yacht Club member, and he spoke of down-to-earth members and beautiful outstations with plenty of moorage, clean showers, uncrowded laundry facilities, and plenty of ice. After a bit of convincing, I plunked down the $100 initiation fee (not a typo, membership is very reasonable when you join at 23).

As it turns out, it’s been one of my best “investments” in boating. For one thing, members get half-off transient moorage at Elliott Bay Marina. This alone has saved me about $500 per month. And the outstations, with power and water and laundry! Eagle Harbor, on Bainbridge Island, has been a favorite. It’s a short walk to restaurants and groceries. Port Madison, at the north end of Bainbridge, is another favorite. So is Gig Harbor. Nights at outstations are free.

I’ve also been a frequent visitor to Blake Island, and a less frequent visitor to other state parks. For $5 per foot per year, boaters in Washington can purchase an annual, unlimited moorage pass. Mooring buoys are $12 per night; docks are $0.60 per foot per night. The annual pass pays back, in the worst case, in only 16 nights.

Unlike SYC outstations, state parks don’t have many amenities. Most don’t have power or water. None have internet or laundry. The key to making life on a state park dock or mooring buoy (or at anchor) comfortable is having the boat set up properly. This means having enough electricity, heat, water, and internet so that life aboard is like life at home, not a campsite in the bush.

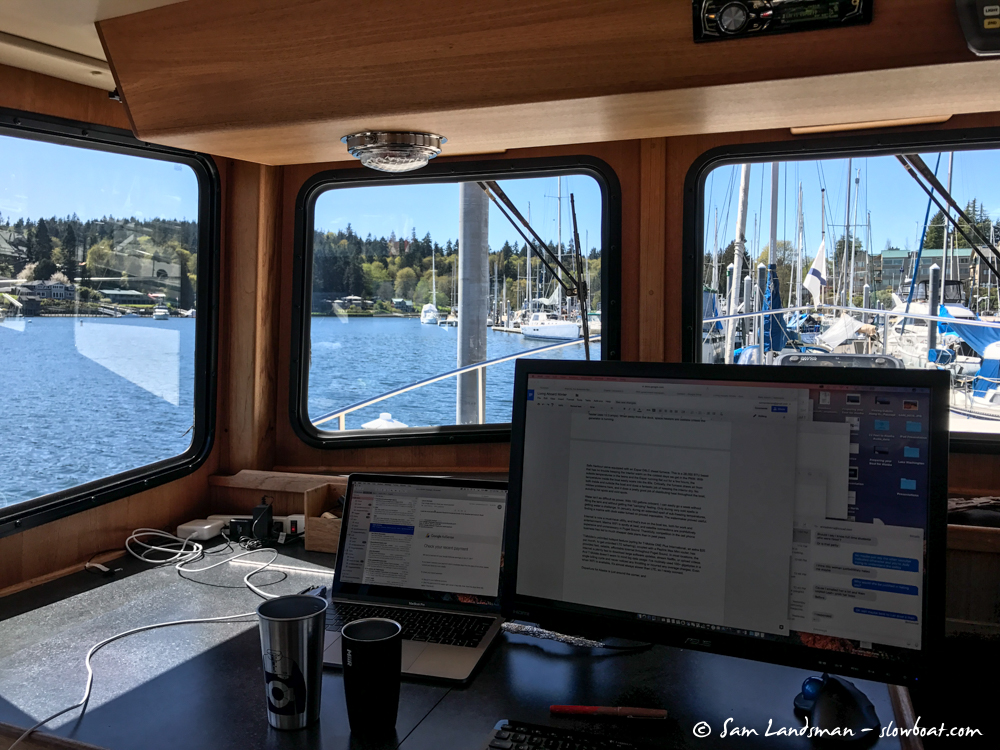

The electrical system is perhaps the most complex and important part of this self-sufficiency. My boat is a power hog (it’s not unusual to use 400+ amp hours per day from the 12-volt batteries), mainly because I don’t like managing power all that closely. Computers, small electronics, networking gear, refrigeration, and diesel heat (the furnace uses nearly 20 amps while running!) are used without concern. The inverter runs 24/7, and provides clean, 120-volt household-type power to every outlet. I use the toaster, coffee maker, and microwave freely, without having to turn on the generator. Not camping, remember?

In the summer, when I’m underway several hours every day, the high-output Balmar alternator recharges the 700 amp-hour battery bank and I seldom use the genset. But in the winter, when I spend several days in one place (and the days are short and cold, so lots of furnace time), the genset earns its keep. Having a reliable, quiet, efficient generator installed on the boat is essential for the way I use the boat. Two to three hours of genset time per day, split between morning and evening, keeps the batteries topped up and the water heater hot.

Compared to most houses, boats are poorly insulated. Windows are typically single pane. If there is any insulation on the hull, it’s probably a thin layer of foam. This winter was particularly wintery. Few things make boating less appealing than being perpetually cold and wet.

When plugged into shore power, and it isn’t too cold, heat is easy: electric space heaters are inexpensive and effective. But the problems with space heaters are multi-fold. For one thing, they use a ton of power. With just a single 30-amp shore power connection, it’s impossible to keep the boat warm enough when the temperatures plunge towards freezing (a single space heater uses 12.5 amps). When away from the dock, space heaters are useless unless the generator is running.

Safe Harbour came equipped with an Espar D8LC diesel furnace. This is a 28,000 BTU beast that has no trouble keeping the interior warm on the coldest days we get in the PNW. With outside temperatures in the teens and the Espar running flat out for a few hours, the temperature inside the boat easily soars into the 80s. Critically, the furnace draws air from both inside and outside the boat and does a fantastic job of keeping the interior dry. No mildew problems here, and it does a pretty good job of distributing heat throughout the boat, avoiding hot spots and cold spots.

Water isn’t as difficult as power. With 150 gallons onboard, I can easily go a week without filling the tank and without getting that “camping” feeling. Only during very cold spells is getting water a challenge. In January, during an extended spell of sub-freezing temperatures, finding a marina with dock water turned on proved impossible. The watermaker proved useful.

Internet is now a must-have utility, and that’s true on the boat too, both for work and entertainment. Marina WiFi is spotty at best, and satellite connections are prohibitively expensive and unnecessary in Puget Sound. Thankfully, competition in the cell phone business has led to much cheaper data plans than in past years.

T-Mobile’s unlimited hotspot feature (spring for T-Mobile ONE Plus International, an extra $25 per month, to get unlimited LTE tethering), coupled with a Peplink MAX router, has provided fast, reliable, affordable internet throughout Puget Sound. In most locations, the internet is plenty fast to download large software updates, stream Netflix, or upload videos. And T-Mobile doesn’t seem to mind big data usage: I’ve routinely used 100+ gigabytes in a single billing cycle and never noticed any throttling or incurred any overage charges. Even when WiFi is available, it’s almost always slower than LTE, so I rarely connect.

Will I go slipless again next winter? It’s too early to say for sure, but I’ve certainly enjoyed the freedom not having a slip affords and the cruising opportunities in Puget Sound. We’ll see how I feel after another summer cruising British Columbia and Alaska…