We left Takatz Bay this morning and headed back to Ell Cove so we could give the hatchery visit another shot. Conditions were gray with fog and light rain. We saw a couple of orcas just outside Takatz, which was nice. Here’s a really bad photo of one of them:

We anchored in Ell Cove, dinghied over to Hidden Falls, and wandered around the hatchery grounds a little before we ran into Jon, the hatchery manager, who spent some time telling us about their operation there.

Before we dive into details about the hatchery, we want to make one thing clear. Hatcheries are a completely different thing from “fish farming.” Fish farming is broadly criticized for damage to the environment, endangering wild salmon runs, and producing poor-quality fish. Hatcheries, on the other hand, are designed to support the natural ecosystem and replace much of the stock that is depleted by commercial fishing.

Without hatcheries, wild salmon would almost certainly be fished to extinction.

Hatcheries, in general, capture fish that have returned from the wild to spawn, fertilize their eggs and nurture their fry, and then release them back into the wild, where they go to the ocean and live their entire lives as wild salmon. After about four or five years, the salmon return as adults to the place they were hatched in order to spawn and die.

The odds for a wild baby salmon to live a full life and return to their birthplace to spawn are incredibly poor. We’re talking “win the lottery” kinda bad odds. Something like 90% of the fry never even make it to the ocean. There are just too many predators out there depending on salmon for food, and too many diseases and environmental factors working against them. A single humpback whale can gulp down thousands of baby salmon in a single lunge.

The ones that make it to the ocean to mature face illegal offshore fishing on a massive scale, as well as numerous ocean predators. Giant miles-long nets can capture hundreds of thousands of fish at a time. This sometimes wipes out an entire wild run in one stroke, as no adult fish are left to return to a particular spawning stream.

In Alaska, commercial salmon fishing is a key industry. They realized long ago that the amount of fishing required to supply the huge worldwide demand for Alaskan salmon would wipe out the wild species entirely. Hatcheries are a critical part of their solution to create and maintain a sustainable supply of wild salmon.

Hidden Falls Hatchery is operated by the Northern Southeast Regional Aquaculture Association (NSRAA), which is “a private non-profit corporation created to assist in the restoration and rehabilitation of Alaska’s salmon stocks, and to supplement the fisheries of Alaska by utilizing artificial propagation to enhance the availability of salmon to all common property users, without adversely affecting wild salmon stocks.”

Hidden Falls is the largest hatchery operated buy NSRAA, and produces Chum, Chinook, and Coho salmon. When we visited, the season was in its very early stages. Chinook (King) fry were being raised in several of their outdoor tanks:

…and a number of Chinook had returned and were being held in a pond as brood stock for later in the season.

Soon, the Coho (Silver) salmon should start returning, and then the activity around the hatchery really picks up. For Chum, for example, something over a half million hatchery fish (from three to five years old) are expected to return this year. Of those, almost 200,000 will be used as brood stock, and the remainder will be left for commercial fishermen to try to capture.

Those ~200,000 brood fish will produce in the hundreds of millions of eggs which will be hatched, nurtured, and released into the wild by the hatchery. Using some simple, very rough math, you can see that hundreds of millions of eggs produce hundreds of thousands of fry returning several years later. That means only something like one in a thousand eggs results in an adult fish that returns to the hatchery as brood stock. Something like five in a thousand return in total, and that leaves something like four in a thousand for commercial fishing.

Despite those scary-sounding numbers, most of those lost fish play crucial roles in sustaining the ecosystem in SE Alaska, providing a key step in the food chain as well as fertilizing the flora. For fishermen, the ROI from hatcheries is phenomenal, with something like a 5:1 return on every dollar they invest in supporting hatcheries.

The hatchery, of course, also attracts bears. This young male, hopeful for fish, watches the water wistfully:

Just on the rocks across the stream we watched this big sow with four tiny cubs. She sat on the rocks while her cubs scampered around her (and on top of her).

We thanked Jon for his time and all the good information, dinghied back to Airship in Ell Cove, then continued on south down Chatham Strait to Red Bluff Bay. (Before we left, Kevin got a couple of aerial shots of Ell Cove.)

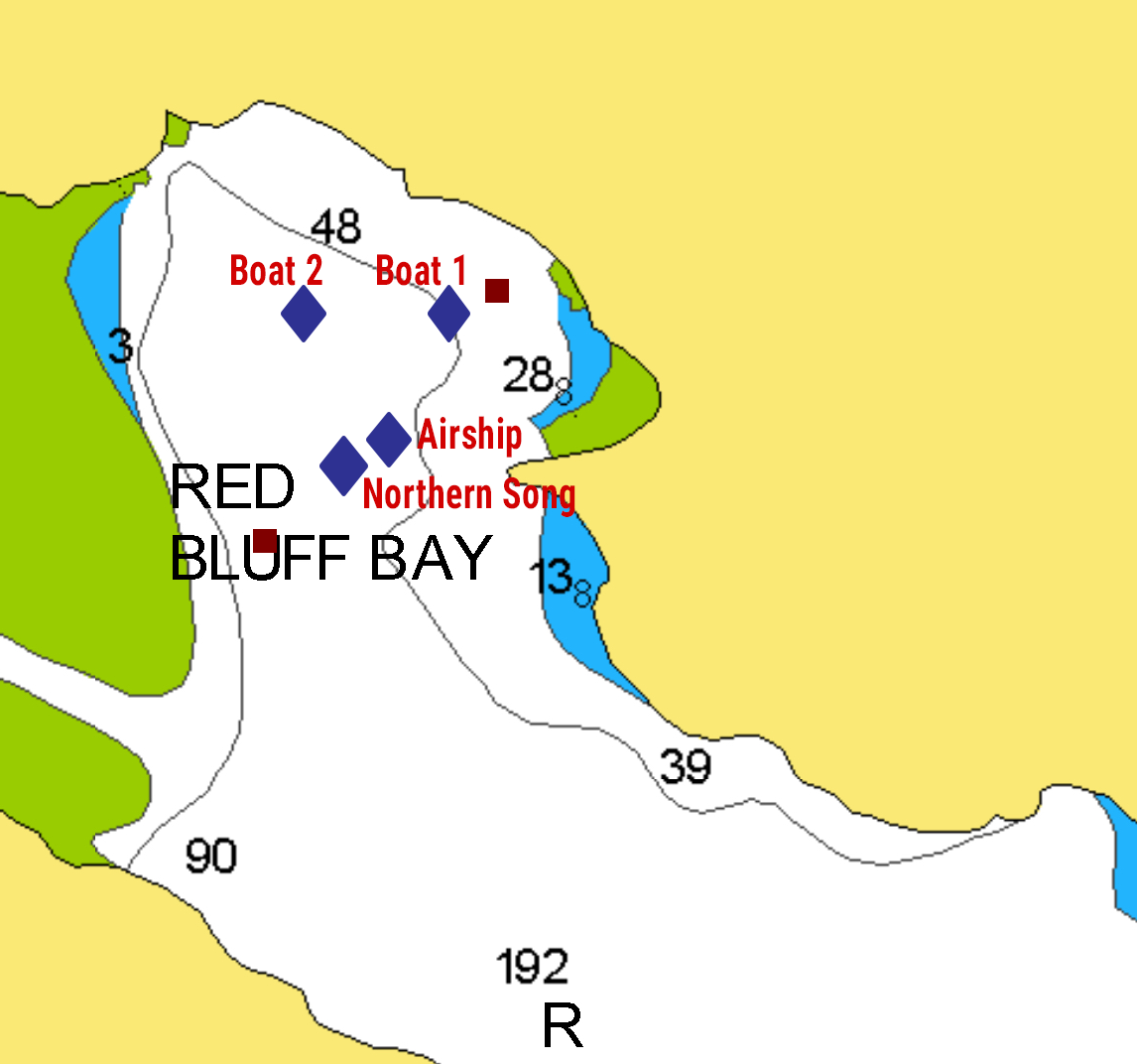

We arrived in Red Bluff bay, where there were two other boats anchored. We turned on the radar and anchored equidistant from them, making a perfect triangle of boats on our chart plotter, then went out in the dinghy to look for bears on shore. We arrived right at high tide, so we were able to go a fair way up the river before it got too shallow. We did not find any bears, but it was sure beautiful.

Back on Airship we started dinner (chicken and spinach enchiladas) just as another large boat entered the anchorage. This boat was Northern Song, an 84′ charter yacht. We passed them on the way into the bay while they were letting out passengers in kayaks. They anchored RIGHT next to us. Like, really, right next to us.

Aren’t these guys professionals? Shouldn’t they know better than to anchor this ridiculously close to another boat, especially since this is a relatively deep anchorage? We were anchored in 90 feet with about a 3:1 scope, meaning our swinging circle at anchor has a radius of well over 200 feet from our anchor. They anchored about 150 feet from where our boat was at the time, according to our radar. Keep in mind, their boat at anchor also has a swinging circle. This means there’s a huge overlap between our swinging circle and their swinging circle. At times, our radar showed their boat sitting right on top of where we dropped anchor. Luckily in an anchorage, boats tend to swing more or less the same way at the same time, although this anchorage has so little wind and current, that the boats do their own thing a little bit more, as you can see in the photos above.

Here’s a diagram of what this basically looked like on our radar:

We kept our radar on with a guard-band alarm, so we’d be alerted by that, rather than by the sound of metal on fiberglass. 🙂