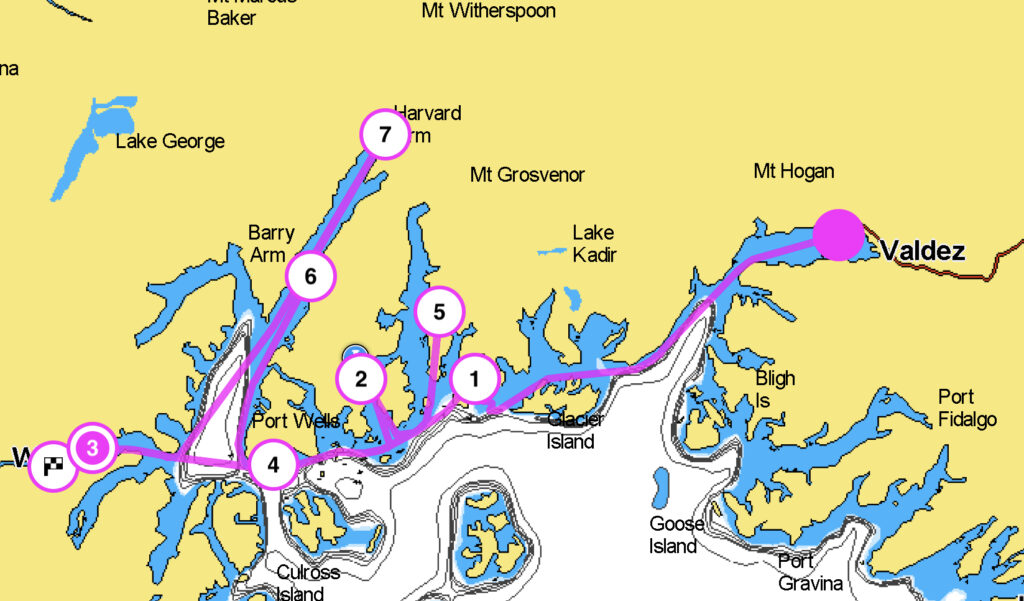

We weren’t in any great rush to leave Valdez. We had breakfast out (a rare treat, no dishes!), provisioned at Safeway (the best grocery shopping in Prince William Sound), and eventually headed to the fuel dock, where we jokingly referred to the diesel as “local, craft-refined” since it’s pulled from the earth in Alaska, sent by pipeline to Valdez, and apparently refined here for the local market. Chores complete, we left Valdez with no firm destination in mind. All we knew was that we had three nights without visitors and needed to end up in Whittier.

Our first stop ended up being aptly named Granite Bay. There are actually several Granite Bays in Prince William Sound, and the one we spent the night at was near the entrance to Unakwik Inlet. We found a spot with fair holding in the outer basin, launched the dinghy, and explored the inner basin.

The next day we moved on to Cascade Bay in Eaglek Bay. The entrance looked somewhat tricky on the chart, which didn’t offer much detail other than a single 12 foot sounding and a few rocks. The guidebook confirmed that it was shallow and suggested to strongly favor the north shore to avoid uncharted rocks. We made it in easily enough, dropped the hook, and spent the afternoon relaxing onboard. Since it was rainy and we weren’t planning on leaving first thing in the morning, dinghy exploring could wait. After a busy month with visitors and covering lots of miles, a lazy day onboard, a good night of sleep, and relaxed morning sounded nice.

About 11:00 p.m., after we were already asleep, we heard air horns blaring and voices shouting. “BEEEEP, BEEEEP, Tsunami, get to deep water!! BEEEP BEEEEP, Tsunami, get to deep water!” Confused, naked, without my glasses, I ran topside and acknowledged the warning. One of the sailboats that was anchored nearby was circling and screaming. When they saw me, they turned for deep water and motored out as quickly as they could in the dying evening light. I hurriedly fired up the engine and nav systems while Anna grabbed my robe and glasses. Then, I went to the bow and pulled 250 feet of anchor chain as fast as I could (does pressing the button harder make the windlass work faster?!?!), periodically glancing at the entrance to see if the big wave was marching in.

I’d read about tsunamis in Prince William Sound. The cruising guide has an entire section devoted to them. In the 1964 quake, tsunamis were generated locally by massive underwater landslides. These struck almost simultaneously with the earthquake and devastated PWS communities like Valdez and Chenega. Mariners had just minutes to act. Other types of tsunamis occur more slowly, from quakes hundreds or thousands of miles away. Standing in my robe on the bow, I had no idea what we were dealing with. I didn’t even know if the tsunami warning was real (we hadn’t had time to verify). What I remembered reading in the guide was that when large earthquakes strike, mariners must assume that a tsunami is imminent until it’s proven not to be. Basically, the consequences of inaction in the event of a real tsunami are so high, that the possibility of one requires action.

So, within a few minutes of waking, we were motoring out of Cascade Bay at near wide open throttle, bound for the nearest deep water. By then we’d heard the Coast Guard broadcast warning mariners to get to high ground or deep water (180 feet deep, FYI). From Cascade Bay, that meant going just a half mile. We went another mile, into 450 feet of water, for good measure. Then we waited and waited. Drifting in the middle of Eaglek Bay we ran the generator and filled with water tanks and looked around. It was a perfectly calm evening, not quite clear, but not rainy. Every time the boat rocked a bit, we wondered if that was the wave. We had internet, and saw that Seward and some other communities were evacuating. The earthquake was a big one–8.2, but so far away from people and civilization that it didn’t do any damage. And ultimately, it didn’t create much of a wave, either. About 1:30 a.m. we got the all clear and returned to Cascade Bay in total darkness.

The biggest lesson we took away was to be prepared to get underway at any time (what would we have done if the dinghy hadn’t been lifted already?) and to have tracking enabled on the chartplotters so it’s easy to find the safe route out, even in a tricky spot or in darkness.

After our midnight excitement, we slept in. We didn’t have to go anywhere, so we relaxed and explored Cascade Bay. The sailors who so helpfully woke us the night before left before we could thank them appropriately (thank you, if you see this!) and we had the bay all to ourselves.

Several salmon creeks run into Cascade Bay and we saw lots of black bears. These bears were more skittish than most we’ve seen, retreating into the woods when we approached by dinghy. When they grabbed a fish, they’d quickly take it away and eat it elsewhere. Based on the number of bears we saw, this must be a popular feeding area.

After a day of R&R in Cascade Bay, we first went in to Whittier to pick up my dad, stepmom, and stepbrother. Whittier was packed, the transient dock full. We used a loading dock (below the hotel) just long enough to get our guests onboard, then headed out to Quillian Bay. The guidebook warned this anchorage gets heavy use by commercial fish boats, but we found just one other boat and a delightful lagoon to explore.

Our original plan for this group of visitors was to cruise College Fjord and Harriman Fjord, but geology conspired against us. We’d read and heard about the Barry Arm landslide risk, and after our tsunami warning a few nights ago, had little appetite for more earth-shaking adventure.

A quick primer on the Barry Arm landslide…

Barry Arm is in Harriman Fjord, which juts off of College Fjord. Barry Glacier sits at the head of Barry Arm and has been retreating for several years. The surrounding hillsides—cliffs, really—were supported by the glacier, but with the glacier gone, the cliffs are unstable. A huge rockslide isn’t big deal if it lands on land, but if it lands in a deep bay, like Barry Fjord, it create a big wave. Thousands of feet in Barry Arm, hundreds of feet in Harriman Fjord, and dozens of feet as far away as Whittier or the head of College Fjord. Geologists don’t know exactly when this landslide will occur, but they say it’s imminent and is likely to be catastrophic, perhaps four times the size of the big wave at Lituya Bay. We certainly don’t want to be nearby when it happens.

To avoid this risk, we went to Unakwik Inlet and Meares Glacier. Somehow, we lucked into five more days of sunshine, warm temperatures, and light winds. We spent the night anchored at the Cow Pens, just a few miles from Meares Glacier.

The guidebook mentioned a hike to a nearby lake. We tried to find the trail, but couldn’t, and instead walked up a creek. About 200 yards in we saw a mama bear and cub and quickly retreated to a small nearby island and then back to the boat. Later, we caught a glimpse of a mama and cub on shore.

Meares Glacier, unlike most tidewater glaciers in Alaska, is advancing. As a result, the scenery is far different from Columbia Glacier or other retreating glaciers. Rather than the stark, bare, glacier-carved cliffs of a retreating glacier, here there are mature forests.

As the glacier advances, it gobbles up the forest. It would be fun to watch a time lapse of the process.

Meares Glacier was gorgeous. We approached as close as we dared, uninhibited by any significant ice. The wind was almost totally calm and the air warm, a rare combination in front of a glacier. We had the whole place to ourselves, except for the seals and sea otters.

We spent a few hours at Meares Glacier, then, inspired by the scenery, decided to risk College Fjord and the Barry Arm tsunami. The weather was perfect, with bright blue skies and unlimited visibility. We figured we’d anchor near deep water, leave the radio on, and skip Harriman Fjord. We anchored for the night at Coghill, about 15nm from the head of College Fjord. This isn’t the easiest anchorage–it’s not well charted and has large drying flats, but we found plenty of room and solitude. We also found a salmon creek, bears, and incredible views.

At high tide we ran the dinghy up the creek as far as we could. Along the way, we saw lots of salmon, and eventually a bear fishing, but it ran away before we got any pictures.

College Fjord is usually a popular destination with cruise ships, but they’re not here this year. We can see why it’s popular, though. Six and seven thousand foot high mountains line the shoreline with numerous glaciers hanging in the valleys above.

Near the head, at College Point, we went straight, to Harvard Glacier. Peaks rise to more than 13,000 feet behind Harvard Glacier. The glacier itself is hundreds of feet tall and thousands of feet wide.

Drifting a quarter mile in front of Harvard Glacier, we listened to the cracks and groans and watched as small pieces calved off. Satisfied, we left Harvard for Yale Glacier, but didn’t get far. The ice was too thick. With lots of time and great weather, we drifted and launched the dinghy and drone for more exploring.

College Fjord was yet another highlight among weeks of highlights. After College Fjord, we dropped Dad, Carrie, and Ben off in Whittier. This time, we had a night to spend, and we lucked into transient space, even 50 amp power. We walked around Whittier and texted Jason, Laura’s brother, who lives nearby in Girdwood. Jason happened to be free, so he hopped in his car and picked us up. He showed us favorite spots in town, took us to a park with thousands of spawning salmon, and we grabbed lunch. Thanks for the great afternoon, Jason!

Next: 52 hours back to Southeast Alaska