Southeast Alaska is among the finest cruising grounds in the world. Stretching more than 300nm from north to south and more than 100nm west to east, it’s a huge and diverse area. Most of it is protected, too, with calm water, relatively easy access to services, and no overnight cruising required. I’ve spent most summers for the last decade exploring SE Alaska and I haven’t seen it all, but Prince William Sound has always beckoned.

Getting to Prince William Sound, however, isn’t easy. Small boats can be shipped by barge or trailered around (when Canada is open), but larger boats must transit the Gulf of Alaska, a body of water not particularly well known for pleasure cruising.

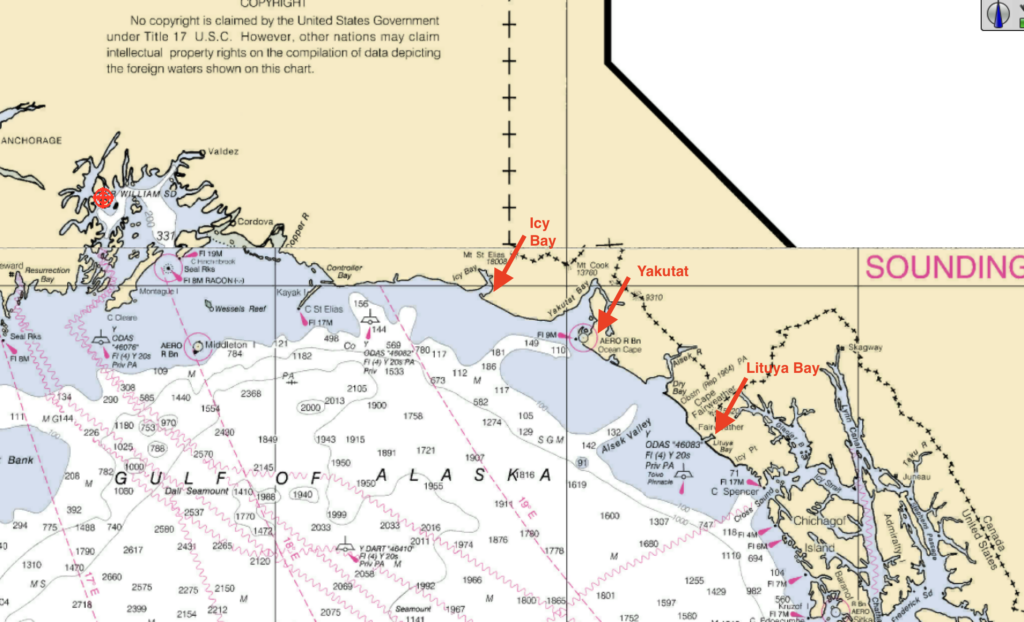

In summer, the Gulf of Alaska can be transited in a series of long day trips if the boat can maintain 8.5 knots. It’s about 55nm to Lituya Bay, the first viable overnight anchorage. Yakutat, the next safe harbor, is another 97nm. The next viable anchorage is Icy Bay, 73nm up the coast. Finally, there’s the 170nm run from Icy Bay to Hinchinbrook Entrance.

The challenge with this plan is it potentially requires many days or even weeks waiting for weather windows for each leg.

An alternative is a 300nm non-stop run, which requires just a single two day weather window.

Weather for our trip dictated a hybrid approach. First we did a day trip to Lituya Bay, then we ran non-stop to Prince William Sound.

Insurance

Most yacht insurance policies end at Cape Spencer. To add coverage for the Gulf of Alaska crossing, my insurer (Chubb) required that I submit cruising resume for each crew member, our planned itinerary, and safety plans. They tripled my deductible and charged an additional premium.

Cruising Guide

The best guide I found for crossing the Gulf is available for free online through the University of Alaska. http://goa-travel.seagrant.uaf.edu

The boat

I’ve never felt more alone than in the Gulf of Alaska and I wouldn’t trade the security of having a boat built for this purpose for anything. On the ocean, even a calm ocean, the design compromises all make sense. That one-butt galley? Perfect for cooking in the swell. The midship master? Super comfortable underway. The Portuguese Bridge? Sure, line handling is a bit more difficult, but going out for some fresh air or checking something out in the binoculars is totally secure. I wouldn’t even think of doing the trip without stabilizers, not because it wouldn’t be safe, but because a comfortable crew is more likely to be a well-rested and safe crew, and we were way more comfortable thanks to the stabilizers.

Taking my wife and two non-boating friends on an ocean passage is a huge responsibility. Knowing that the boat is built for it, has backup propulsion and steering, strong windows, and a ballasted full keel brings incredible peace of mind. Could I have done the trip on Safe Harbour (my old Nordic Tug 37)? Sure, but it wouldn’t have been nearly as comfortable or had the same margins of safety.

Weather

Weather is the single biggest challenge with a Gulf of Alaska crossing. I utilized PredictWind and Windy extensively to select a weather window. Both applications have route planning functions that allow you to input your route and speed. Then you can “walk through” the voyage, seeing what wind and wave conditions are forecast for each hour of the trip where you’ll be. Windy needs internet for this, but PredictWind can be done via their Offshore app and Iridium satellite service.

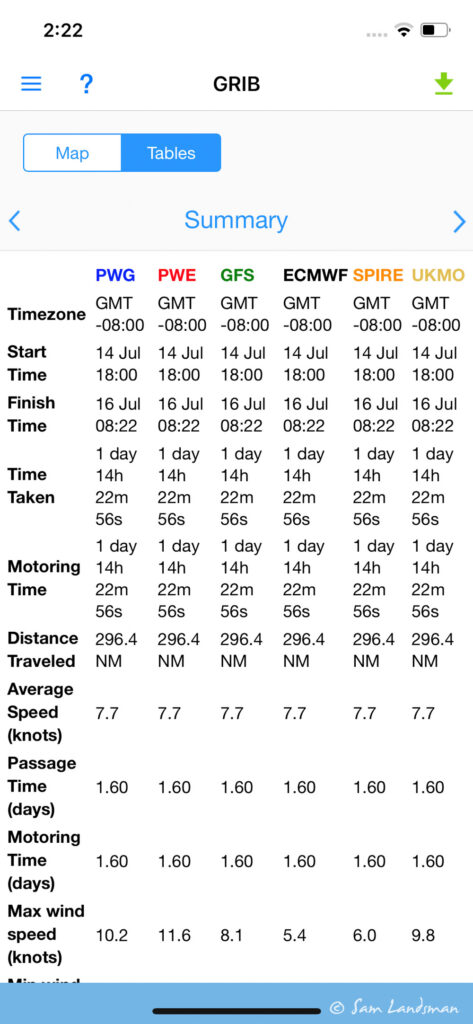

The PredictWind Offshore app and Iridium Go! are a super powerful combination for getting weather information offshore (and also phone calls, limited email, and text messaging). In past years I’ve used a Garmin InReach for basic texting and weather. Iridium Go! and PredictWind Offshore cost quite a bit more, but deliver so much more that they’re worth it for offshore travel. Being able to download ECMWF GRIB files, weather routes, etc. anywhere is invaluable. Here’s an example of the route summary when we left Lituya Bay:

To Lituya Bay

Of the three anchorages along the Gulf of Alaska, Lituya Bay was the most intriguing for me, and also the most difficult to access.

Lituya Bay’s history is filled with tragedy. French explorer Lapérouse explored the bay in 1786, hoping he’d find the Northwest Passage. After entering the bay, 21 of his crew set out in small boats to survey the area. As they approached the entrance to Lituya Bay, a strong ebb current was running, which swept them out to sea, where the boats foundered and capsized in the steep, breaking seas. All 21 men were killed. Our cruising guide ominously warns: “The first thing to know about the Lituya Bay entrance is that it has killed many people.”

The key to entering Lituya Bay, apparently, is to avoid the ebb, when hazardous conditions prevail. I’ve read this in the guide, but also heard it from two experienced captains who’ve been here before. So we timed our departure from Flynn Cove and then adjusted speed en route to arrive at Lituya Bay an hour before high water slack. Since the waiting room here is the swelly ocean, there’s no great incentive to arrive early, but arriving late means not getting in and continuing to Yakutat.

The tricky entrance isn’t the only intriguing aspect of Lituya Bay. In 1958, the world’s tallest tsunami was recorded here when an earthquake triggered the side of a mountain to fall into the bay. The wave created by this event briefly reached 1700 feet high. Several boats were anchored in Lituya Bay at the time. Only one survived. Even today, evidence of the wave persists in the form of a distinct band of younger trees growing from the waterline to several hundred feet of elevation.

Conditions for our trip to Lituya Bay were only fair. No wind, but a five foot swell at about seven seconds. The stabilizers worked hard, but motion aboard the boat was still significant. Moving around required one hand for the boat. We all hoped the forecast for better weather for the next, long leg would hold true.

Just as planned, we arrived at Lituya Bay about 4:00 p.m., one hour before high slack. The entrance is intimidating. The safe channel is only about 150 feet wide, and swells crash mercilessly on huge boulders on either side of the entrance channel. The dying flood current sets you onto the rocks. Loss of propulsion or steering would quickly be catastrophic here. For the first time ever, I fired up the wing engine before entering, just in case. My concern was, thankfully, unwarranted. Akeeva motored easily across the bar, and in a matter of moments we were out of the swell and into Lituya Bay.

We cruised past the north side of Cenotaph Island and found a good anchorage in 50 feet along the north shore of Lituya Bay. And then we explored!

Lituya Bay was last surveyed before the 1958 mega tsunami and its hugely different than the charts indicate. Neither Gilbert Inlet nor Crillon Inlet exist anymore. They’re now completely filled with boulders and silt, and the glaciers that once touched the ocean are several miles away. Still, a few small bergie bits get flushed out into the bay, something I’d not expected or read about.

These two panoramas attempt to capture the scene at the head of Lituya Bay:

We spent about 24 hours in Lituya Bay, all alone, feeling like the only people on the planet. Evidence of geologic instability is everywhere. Near the head of the inlet, we listened to pops and watched rock tumbling off the cliffs. Rock slides dot the hillsides. Apparently the 1958 slide and wave were not isolated events: the Tlingit once had a village in Lituya Bay, but abandoned it after repeated destruction by large waves. We couldn’t help but feel tiny and totally insignificant in this place, fortunate to be able to experience it for a day, but grateful to move on safely.

300nm Across the Gulf

Exiting Lituya Bay was easier than entering, thanks to a smaller swell and having a safe track to follow. We quickly turned west-northwest towards the tip of Kayak Island and settled in for 36 hours on the ocean.

Calm ocean passages are magical. The swell slipping under the boat, watching the sun set and then rise, the sense of independence and solitude. The outside world melts away, it’s just us and the ocean, and we’re singularly focused on the present. Nowhere else have I experienced the same feelings of contentment.

The weather forecast showed improving conditions throughout our transit, with the swell subsiding from one meter to just half a meter and the period increasing from 7 seconds to 11 second. Sure enough, conditions kept getting better. For the first 24 hours, we barely had a breath of wind and the swell gently rocked the off-watch crew to sleep. We enjoyed an unexpected but significant boost in speed from the current, too.

The hours slipped by fairly effortlessly. When we left Lituya Bay, I plotted Port Etches, the first all-weather anchorage in Prince William Sound, as our destination. But as it became clear that we’d be well-rested and arriving in the wee hours of the morning, we decided to add a few hours and press further into the sound.

We never totally lost sight of land, even 40 miles offshore. Because the Fairweather Range is so massive—Mt. St. Elias is 18,008 ft, Mt. Logan is 19,850—they’re visible from a long way away. Much of the trip, we could look towards shore and see rugged, snow covered mountains.

We arrived at Hinchinbrook Entrance at first light and rode the dying flood in. Perfect timing, since this area apparently gets bumpy when the ebb collides with ocean swell. Soon, the swell was gone entirely and we enjoyed a perfectly calm several hours of motoring to Drier Bay, on Knight Island, where we dropped the anchor in Barnes Cove. Josh made homemade bagels on the way across the Gulf, so after 350nm (356.4nm in 41 hours, 44 minutes) underway, we sat in the sun, ate bagels, and drank champagne to celebrate our arrival.