One of the most important skills for successful cruising is understanding the weather and how it impacts your plans. This doesn’t mean being a meteorologist, making your own forecasts, or interpreting esoteric weather charts. Rather, it means selecting the right forecast from professional meteorologists (NOAA, Environment Canada, European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts), utilizing real-time weather data from the multitude of weather reporting sites along the coast, and adjusting cruise plans accordingly. Below is the process we use to gather and interpret the myriad information available.

Look ahead. Preparation for crossing any of the gates in the Pacific Northwest starts many days before the planned voyage.

The first step is checking the NOAA and/or Environment Canada forecasts. Some routes require looking at several different forecast areas. If it’s a particularly complex area, we may go as far as writing down the forecast for each zone for the next several days to make the information clearer and easier to recall. Our Weather Worksheets (see more below) make this easier.

The next step is visiting Windy.com or using the Windy app. We detailed some tips for using Windy in this article, so we won’t repeat them all here. The short version is that we switch the view to “wind gusts” and browse through all three models: NAM, GFS, and our favorite, ECMWF. We step through the forecast hourly, looking at trends and predicted changes for the next four or five days.

How does Windy compare to the NOAA or Environment Canada forecasts? How does the weather on your scheduled day look? Do the few days before or after look substantially better? If so, can you adjust your schedule?

Use the Environment Canada Marine Weather Guide. Environment Canada publishes a useful two-page marine weather guide, available here. This guide shows what each forecast zone covers, where weather reporting sites are, and more. We keep a copy at the helm to make it easier to interpret the continuous marine broadcast.

Be flexible. Perhaps more than most cruisers, we embark on most voyages with what seems to be a strict schedule. We’re already planning to round Cape Caution on May 10th, for instance. But the itinerary is much more flexible than it appears at first glance.

Several years ago we were at Pierre’s Echo Bay, scheduled to go to Port McNeill the following day, then round Cape Caution. The forecast for the day we were scheduled to go to Port McNeill was good, but the day we were supposed to round Cape Caution was lousy, with strong northwesterlies. And the extended forecast looked worse. If we stuck to our schedule, we’d get beaten up, or we’d be stuck in Port McNeill for four or five days. Neither was desirable. Instead, we considered slowing down and spending some extra days in the Broughtons or speeding up, skipping Port McNeill, and heading around Cape Caution ahead of schedule. We opted for the latter, and had a long but calm day around Cape Caution from Pierre’s to Fury Cove.

The goal with this flexibility is to avoid being “stuck” somewhere. If you know you’ll be waiting in Naniamo to cross the Strait of Georgia, for instance, consider seeing more of the Gulf Islands first. There’s no reason to hurry up and wait, and many people get antsy when they’re stuck in port, leading them to venture out in less-than-ideal conditions.

Don’t rely on the forecast. Forecasts are theoretical; observed conditions are not. Never embark on a trip across one of the gates solely based on a good forecast. We’re fortunate to have numerous weather reporting sites that provide a wealth of information on wind speed, direction, sea state, and visibility. Use these resources! Unfortunately, some are hard to find. Here are some tips.

NOAA’s National Data Buoy Center (www.ndbc.noaa.gov) shows weather buoys on an interactive map (not mobile friendly). Weather buoys provide information in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, Queen Charlotte Sound, Dixon Entrance, and the west coast of Vancouver Island.

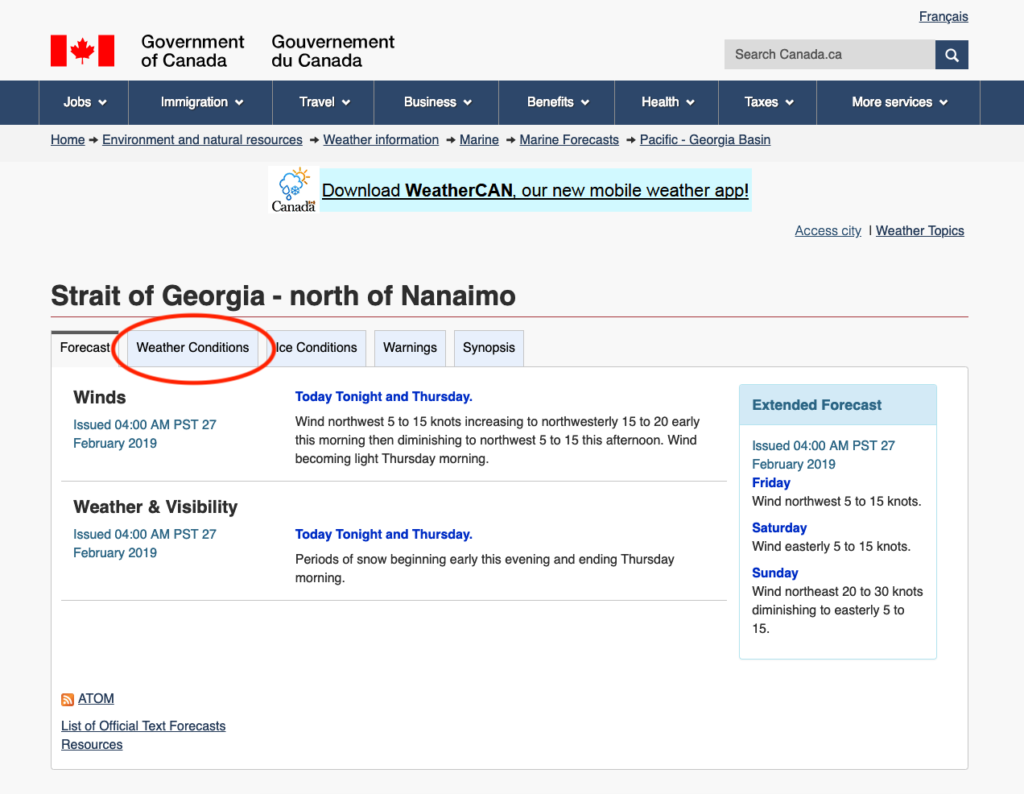

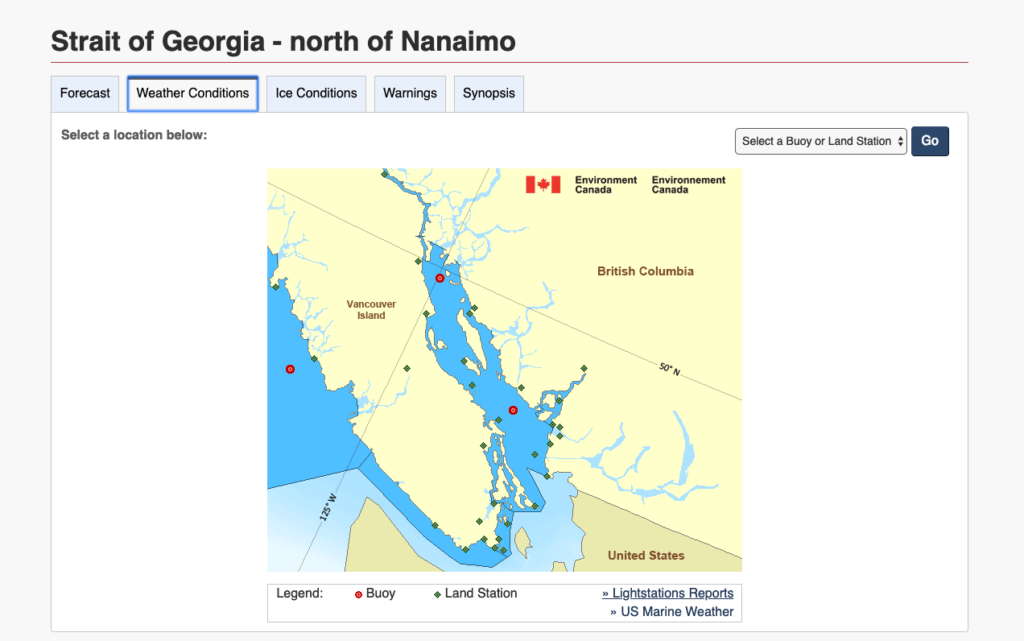

When in Canada, we use Environment Canada’s website. The forecasts are easy to find, but current conditions are buried a little deeper. The first step is clicking the “Weather Conditions” tab:

This page shows up. Click on the green diamonds (land-based weather reporting sites) or red circles (weather buoys) for detailed reports.

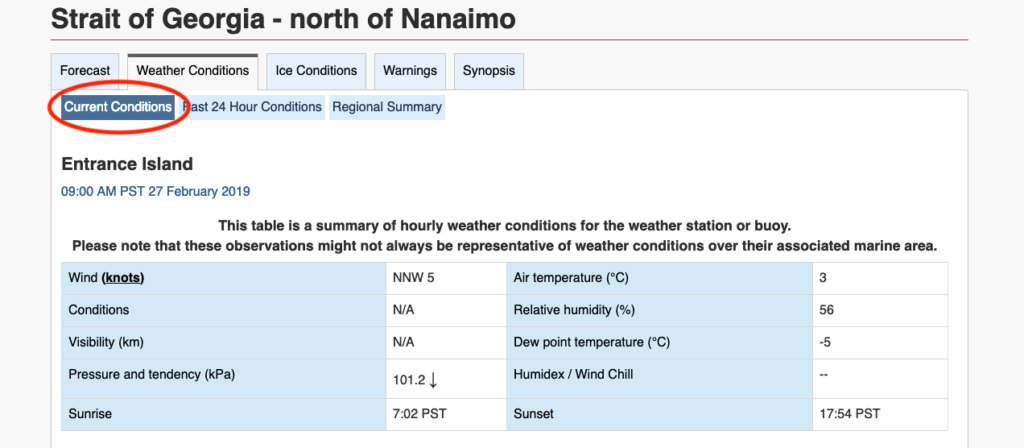

Clicking on a site on the map above brings you to current conditions. Make sure you check the time of the most recent update (in local time) and the wind speed units (depending on how you get to the page, wind speed may be in knots or kilometers per hour…a big difference).

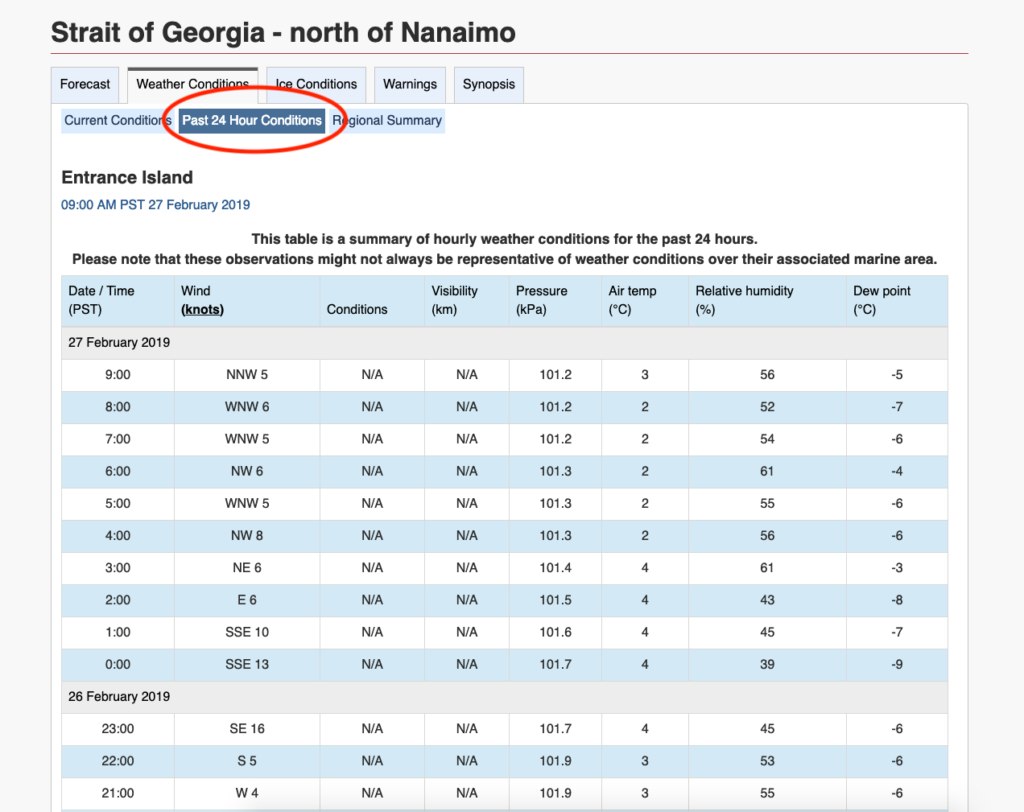

Looking at conditions over the past 24 hours can be helpful, too. Did the wind change as predicted? How closely do the observed conditions match what was forecast?

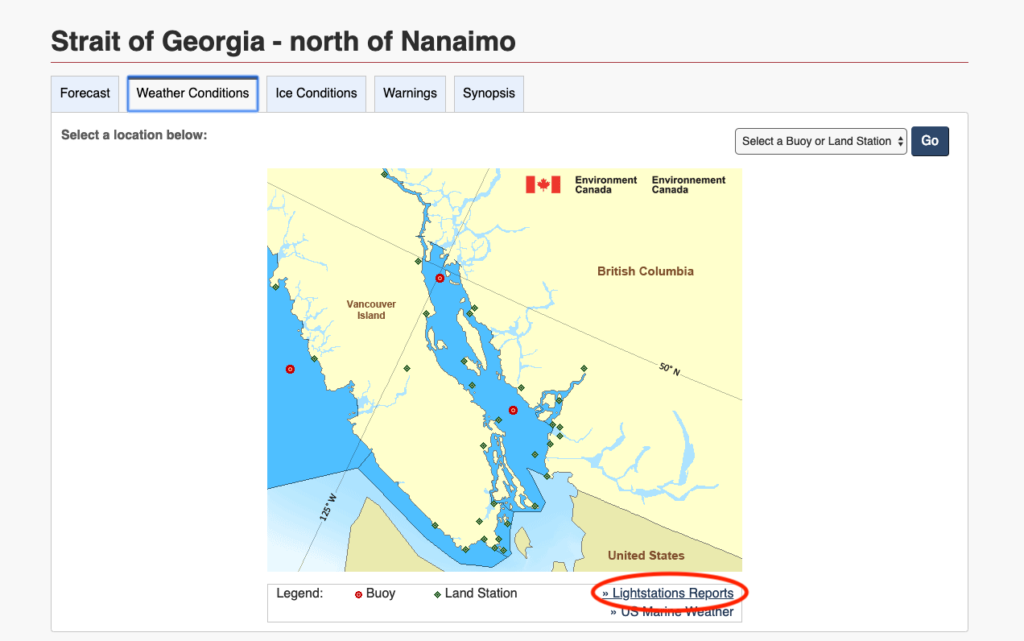

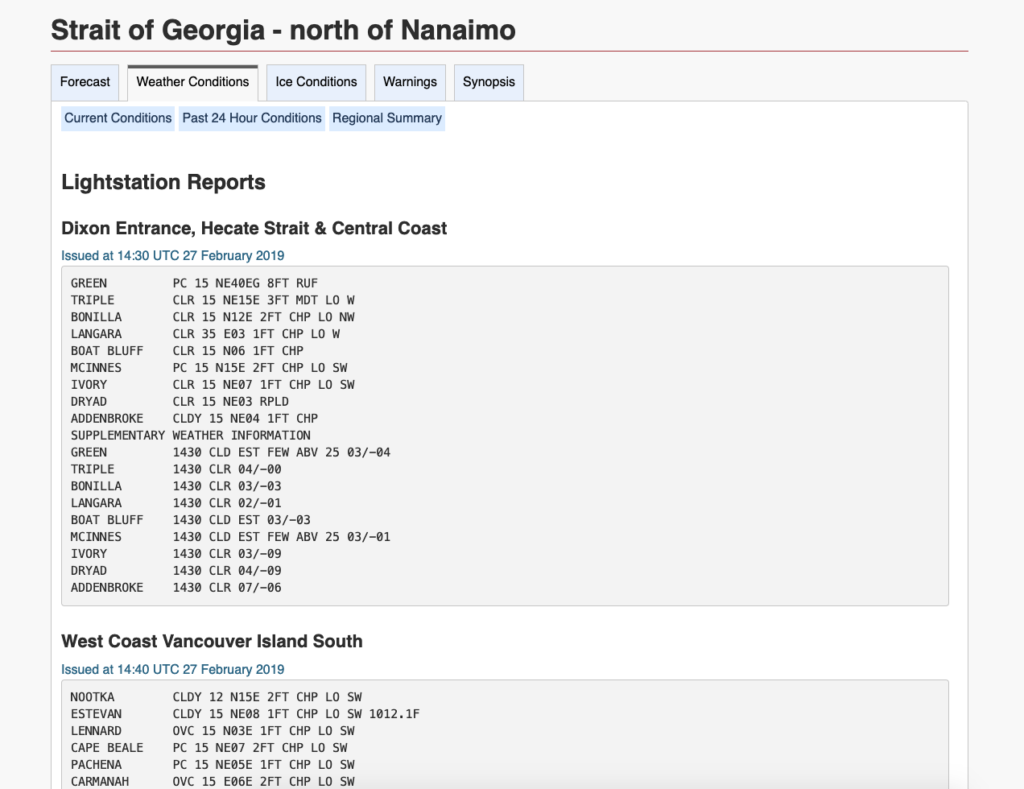

Back on the main “Weather Conditions” tab is a small, nearly hidden link to “Lightstations Reports.” Canadian lightstations are manned, and the lightkeepers file weather reports every three hours.

Clicking on the Lightstations Reports tab opens the page below. This info can be hard to digest, but here’s the quick interpretation of the Green Island report (PC 15 NE40EG 8FT RUF): PC means partly cloudy, 15 is the visibility in miles, NE is NE wind, 40 is the wind speed in knots, E means the speed is estimated, and 8FT RUF means the wind waves are 8 feet. Sometimes these reports include information on fog, smoke, rain, or other weather. Click here for key to decode it all.

Keep in mind that the time used for these reports is UTC and they’re a qualitative assessment from a human lightkeeper. If you’re looking first thing in the morning, be sure the report has updated and you’re not looking at data from last night. As a general rule, we find 3 foot moderate is the point where cruisers start talking about rough conditions and 4 foot moderate is no fun.

No internet? Even when there’s no internet, most of this information is available on the continuous marine broadcast. Click through the weather channels on your VHF to find the best frequency and listen patiently. Alternately, some of this data is available using SiriusXM marine weather and weather buoys can be accessed by phone (satellite phones included) using dial-a-buoy. When all else fails, we have occasionally texted friends or family at home using the inReach and asked them to look at the weather forecast or conditions and forward them to us.

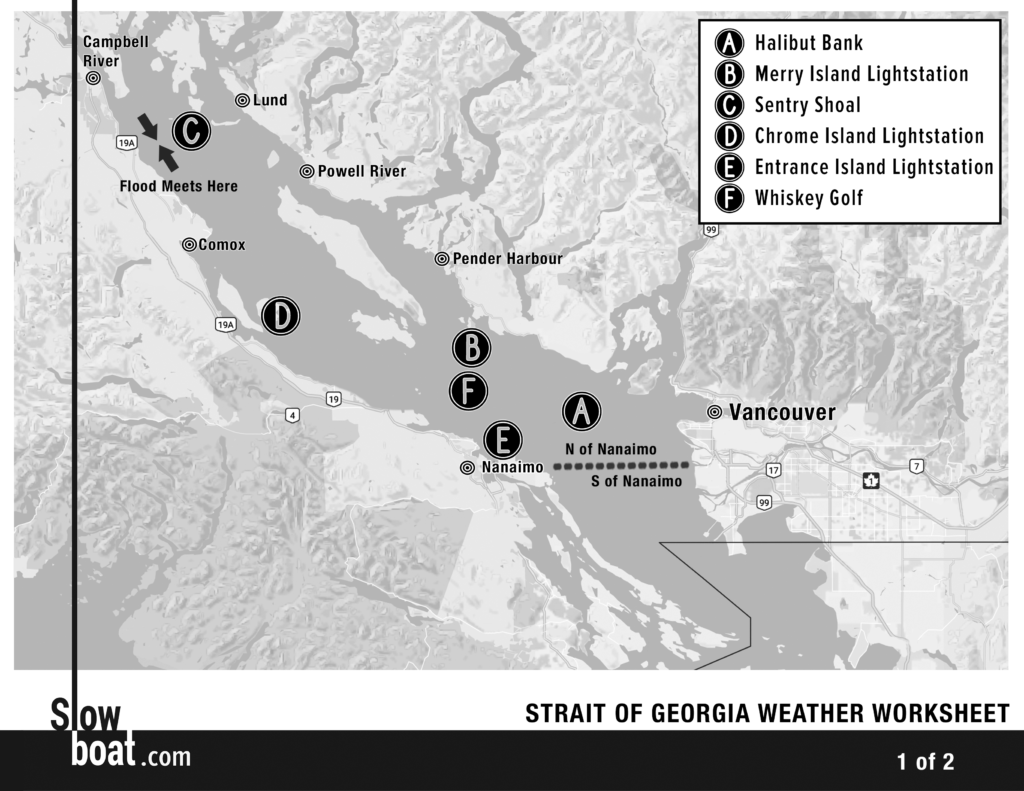

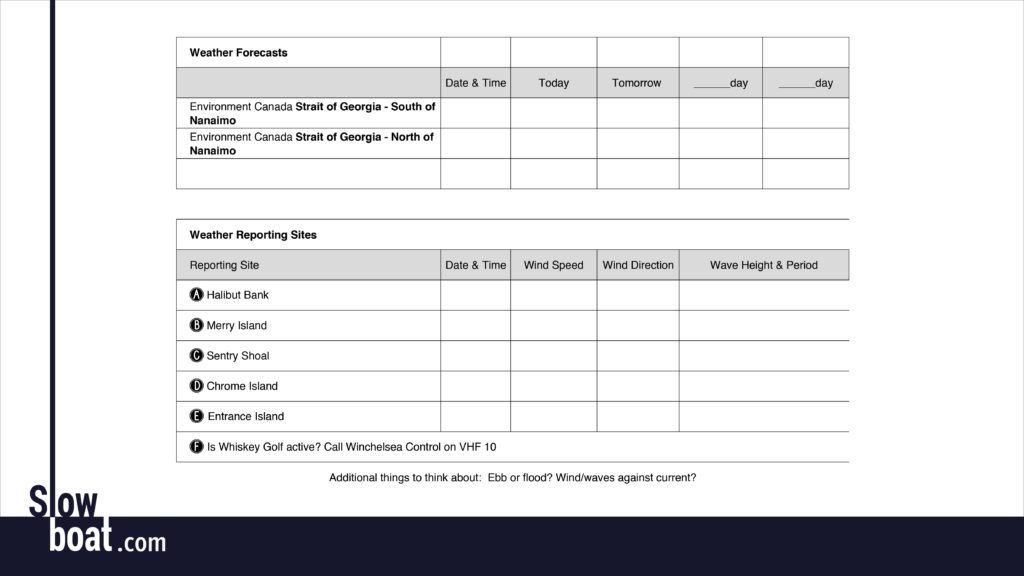

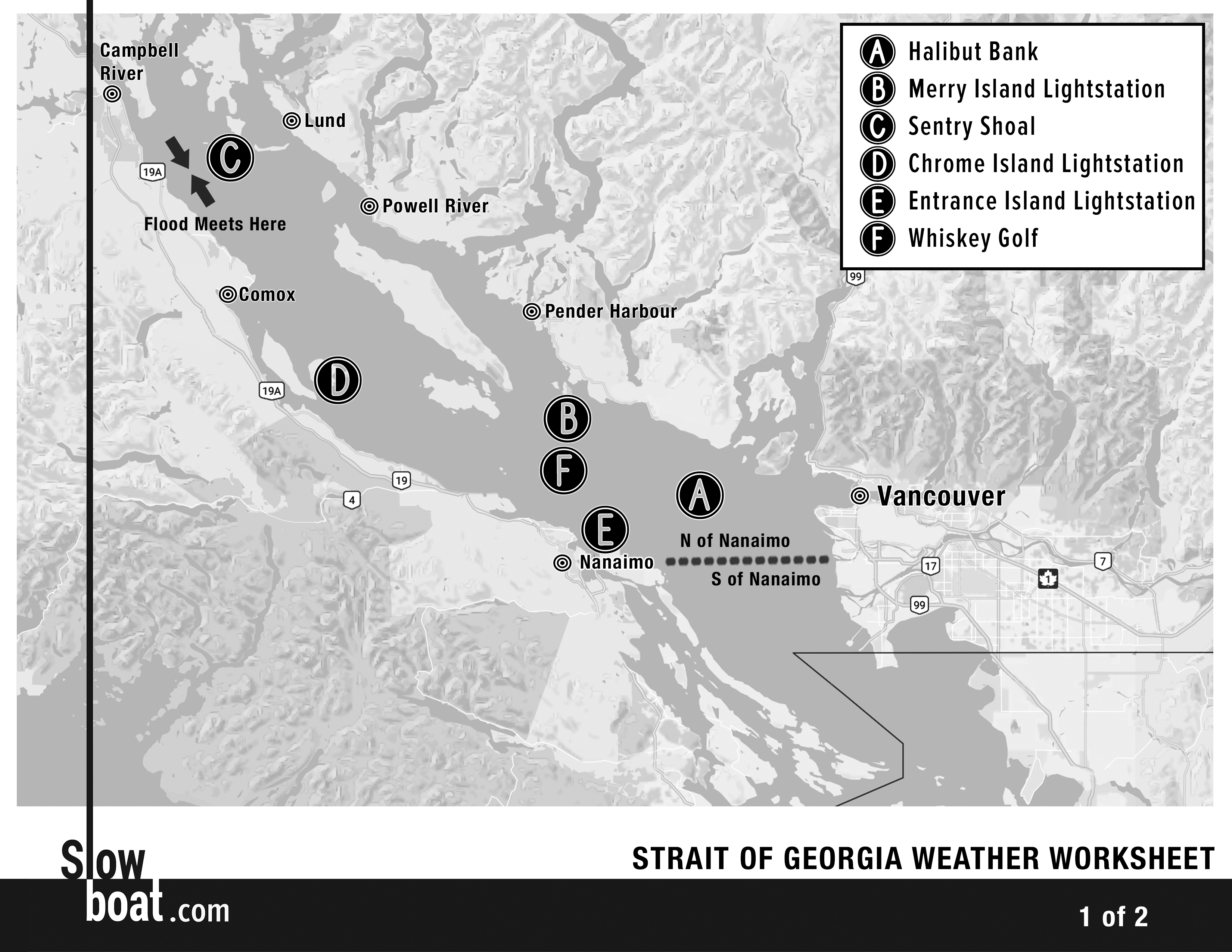

Slowboat Weather Worksheets. The biggest challenge to selecting a good weather window is synthesizing the forecasts and observed conditions into something useful. We’ve created Weather Worksheets for the Strait of Georgia, rounding Cape Caution, and crossing Dixon Entrance that make this easier. Download the worksheet, print it out, and then click away (or listen to the continuous marine broadcast) to fill it out. We also have webinars describing strategies for dealing with each of the gates. Scroll down on these webinar pages (Strait of Georgia, Cape Caution, Dixon Entrance) to see the Weather Worksheets and scroll down further to links to pertinent weather reporting sites.